9 Conditioning

9.1 Defining conditional expectations

9.1.1 Given event

Assume we know that \omega \in H for some H\in \mathcal H. We modify the notion of \mathbb E_H X = \frac{1}{\mathbb P(H)} \int \mathbb 1_H(\omega) X(\omega) \mathbb P(d\omega) = \frac{\mathbb E[\mathbb 1_H X]}{\mathbb P(H)}

If instead we know whether \omega it is in H or H^c, then \bar{X} is a random variable: \bar{X}(\omega) = \mathbb 1_H(\omega) (\mathbb E_H X ) + \mathbb 1_{H^c}(\omega) (\mathbb E_{H^c} X )

9.1.2 Given \sigma algebra

Consider probability space (\Omega, \mathcal H, \mathbb P). Let X: (\Omega, \mathcal H) \rightarrow (\mathbb R, \mathcal B_R) be a positive random variable. Let \mathcal F \subset \mathcal H be a sigma algebra.

The conditional expectation of X conditioned on \mathcal F is any random variable \bar{X} (called a version) such that these properties hold:

- Measurability: \bar{X} \in \mathcal F_+

- Projection: for every set H \in \mathcal F: \mathbb E[\bar{X} \mathbb 1_H] = \mathbb E [X \mathbb 1_H] (or equivalently for every positive measurable function V: \mathbb E[\bar{X} V] = \mathbb E [X V]).

The conditional expectation always exists and is unique upto almost sure equivalence.

Proof of existence

Let X \in \mathcal H_+, \mathcal F \subset \mathcal H.

Define measures \mu, \nu on (\Omega, \mathcal F), such that for V \in \mathcal F: \mu[V] = \mathbb P[V] \nu[V] = \int V(\omega) X(\omega) \mathbb P(d\omega)

\nu is dominated by \mu, which is \sigma-finite. Thus by the Radon Nikodym theorem, there exists \frac{d\nu}{d\mu} \in \mathbb F_+ such that:

\mathbb E[VX] = \nu[V] = \mu[V \frac{d\nu}{d\mu}] = \mathbb E[V \frac{d\nu}{d\mu}]

Thus \frac{d\nu}{d\mu}(\omega) is a positive \mathbb F measurable random variable that satisfies the projection property.

9.1.3 Given random variable

Let X: (\Omega. \mathcal H_+) \to (\mathbb R, \mathcal B(\mathbb R)), Y: (\Omega. \mathcal H_+) \to (E, \mathcal E).

The conditional expectation given a random variable is the same as conditional on the sigma algebra generated by the random variable. \mathbb E [X | Y] = \mathbb E_{\sigma Y} [X] \mathbb E [X | \{Y_t : t \in T\}] = \mathbb E_{\sigma \{Y_t : t \in T\}} [X]

Since the resulting version has to be measurable wrt \sigma Y, we can write it as f\circ Y for some measurable g \in \mathcal E_+.

Conversely, g \circ Y is a version of \mathbb E_{\sigma Y} [X] if and only if for every v \in \mathcal E_+ (corresponding to every V \in \sigma Y):

\mathbb E[ (g\circ Y) (v \circ Y) ] = \mathbb E[ X (v \circ Y) ]

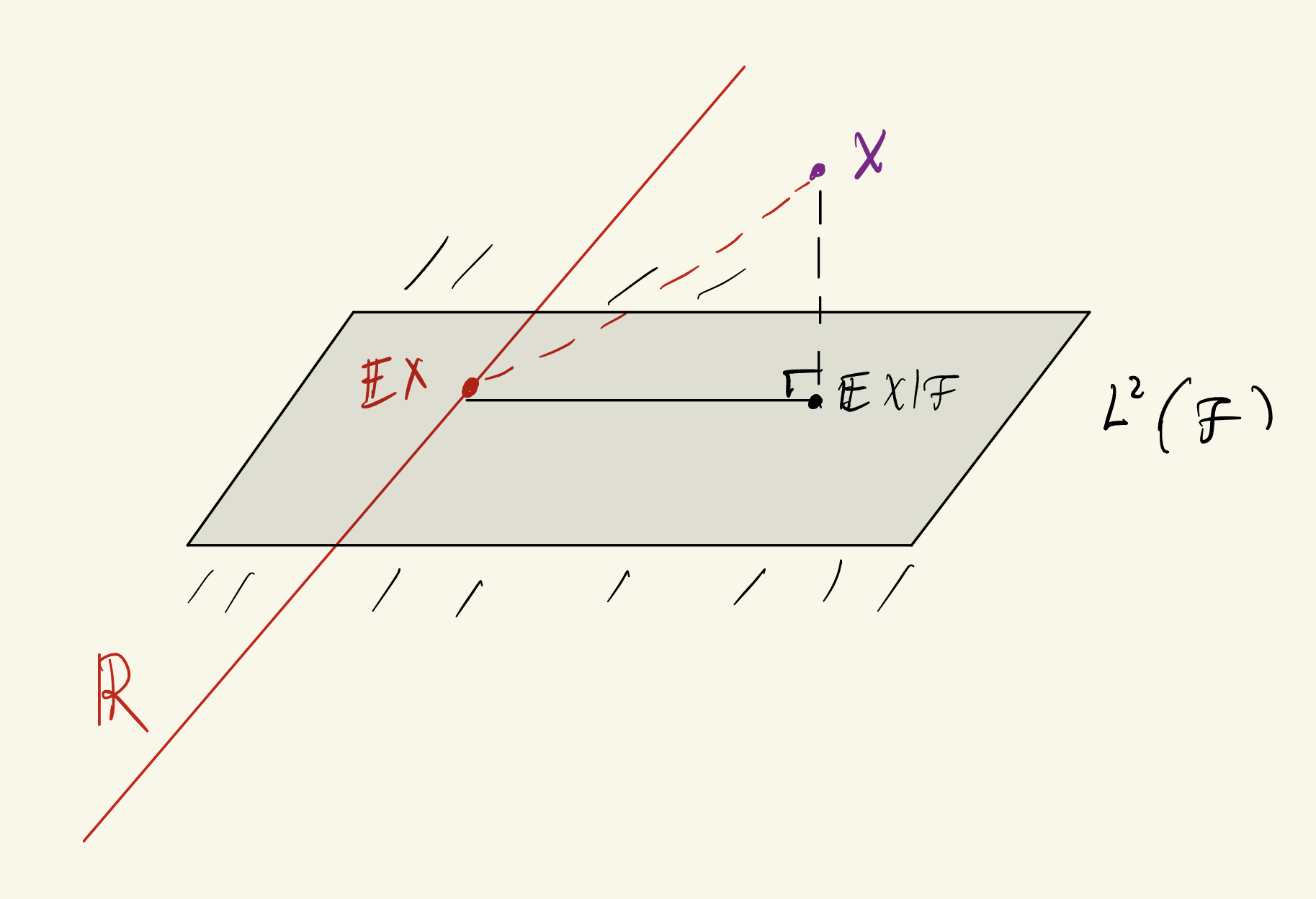

9.1.4 Squared error interpetation

For every square integrable random variable X, there exists a unique (u.a.s.e) \bar{X} \in L^2(\mathcal H) such that:

\mathbb E[X- \bar{X}]^2 = \inf_{Y \in L^2(\mathcal F)} \mathbb E[ X- Y]^2

and X-\bar{X} is orthogonal to L^2(\mathcal F) i.e. for all V \in L^2(\mathcal F), \mathbb E[V(X- \bar{X})] = 0

9.1.5 Law of total variance

For every square integrable random variable X, we have

\text{Var}(X) = \mathbb E[\text{Var}(X|\mathcal F)] + \text{Var}(\mathbb E[X|\mathcal F])

where the conditional variance is defined as:

\text{Var}(X|\mathcal F) = \mathbb E[X^2|\mathcal F] - (\mathbb E[X|\mathcal F])^2 = \mathbb E[(X- \mathbb E[X|\mathcal F])^2]

Proof

Variance is the distance in L^2 to the vector space of constant random variables.

We have \text{Var}(X) = \min_a \mathbb E[(x-a)^2]

Now \mathbb R \subset L^2(\mathcal F) \subset L^2(\mathcal H) i.e. the constant random variables are a subspace of the \mathcal F measurable random variables, which are a subspace of all random variables.

Let the conditional expectation \bar{X} = \mathbb E[X|\mathcal F], which we know is the projection of X onto L^2(\mathcal H). Also, \bar X- \mathbb E[X] and \bar X- X are orthogonal:

Then by the Pythagorean theorem in Hilbert spaces, we have:

\mathbb E[X- \mathbb E[X]]^2 = \mathbb E[X- \bar{X}]^2 + \mathbb E[\bar{X} - \mathbb E[X]]^2 = \text{Var} ( X|\mathcal F) +\text{Var} (\bar X)

9.2 Properties of conditional expectation

9.2.1 Conditional determinism

W \in \mathcal F \implies \mathbb E_\mathcal F [WX] = W \mathbb E_\mathcal F [X]

9.2.2 Iterated conditioning or coarsening

If we successively take conditional expectations with respect to two sigma algebras \mathcal F \subset \mathcal G, this corresponds to taking a conditional expectation only on the coarser one.

\mathbb E_\mathcal F [\mathbb E_\mathcal G [X] ] = \mathbb E_\mathcal G [\mathbb E_\mathcal F [X] ] = \mathbb E_\mathcal F [X]

The intuition is that taking a conditional expectation is a coarsening/compression operation on a random variable. The coarser (smaller) the sigma algebra, the more discretised the result. The larger the sigma algebra (the more information it contains about \omega), the more information we preserve.

In the coarsest possible case- the trivial sigma algebra- the conditional expectation is a constant random variable =\mathbb E[X]. In a fine enough case, say \sigma X, all the information is preserved and we get the original random variable back as our conditional expectation.

Applying a finer then coarser conditional expectation causes us to go to a progressively lower resolution. After applying a courser conditional expectation, we’ve already smoothed the random variable, but applying conditional expectation with respect to a finer sigma algebra doesn’t cause further smoothing because of conditional determinism.

The tower property (total expectation) is a straightforward corollary of this.

9.2.2.1 Properties of expectations (with caveats)

For every version:

- Linearity: \mathbb E_\mathcal F [aX + bY +c] \stackrel{\text{a.s.}}{=} a \mathbb E_\mathcal F [X ] + b\mathbb E_\mathcal F [Y] + c

- Insensitivity: X \stackrel{\text{a.s.}}{=} Y \implies \mathbb E_\mathcal F [X] \stackrel{\text{a.s.}}{=} \mathbb E_\mathcal F [Y]

There exists versions satisfying:

- Monotonicity: X \geq Y \implies \bar{X} \geq \bar{Y}

- Monotone convergence: X_n \geq 0, X_n \nearrow Y \implies \bar X_n \nearrow \bar{Y}

- Fatou’s lemma: X_n \geq 0 \implies \mathbb E_\mathcal F \lim \inf X_n \leq \lim \inf \mathbb E_\mathcal F [X_n]

- Dominated convergence:

- Jensen’s inequality (convecx f): \mathbb E_\mathcal F[f(X)] \geq f(\mathbb E_\mathcal F [X])

9.2.3 Miscellanous results

- An (unconditional) expectation is just a conditional expectation given the trivial sigma algebra \{ \emptyset, \Omega\}

- The conditional expectation of a random variable X given a sigma algebra \mathcal G \supset \sigma X, is the exact value of the random variable. More generally \mathbb E[f(X) | \sigma X]= f(X)

- If \mathcal F \subset \mathcal G and \mathbb E[ X| \mathcal G] \in \mathcal F then \mathbb E [X| \mathcal F]= \mathbb E [X| \mathcal G].

- If a random variable X is independent of a sigma algebra \mathcal G \perp \sigma X then \mathbb E[f(X)|\mathcal G] = \mathbb E[f(X)].

Proof

Since \sigma X \perp \mathcal G, for V\in \mathcal G and measurable f:

\mathbb E[f(X)V] = \mathbb E[f(X)]\mathbb E[V]

Now, we can verify that \mathbb E[f(X)] is a version of \mathbb E[f(X)| \mathcal G]

- The constant \mathbb E[f(X)] is trivially measurable with \mathcal G.

- Projection: \mathbb E [\mathbb E[f(X)] V] =\mathbb E[f(X)] \mathbb E[V] = \mathbb E[f(X)V]

9.3 Conditional probability

9.3.1 Conditional measure

\mathbb P_{\mathcal F}(H) = \mathbb E_{\mathcal F}[\mathbb 1_H]

9.3.2 Regular version

If we can express the conditional probability measure \mathbb P_{\mathcal F} as a probability kernel Q from (\Omega, \mathcal F) to (\Omega, \mathcal H), where Q(\omega, H) is a version of \mathbb P_{\mathcal F}(H) for every H\in \mathcal H, we call that a regular version.

If Q is a regular version then QX is a version of \mathbb E_{\mathcal F} [X] for all X \in \mathcal H whose expectation exists. QX = \int Q(\omega, d\omega') X(\omega')

If (\Omega, \mathcal H) is a standard measurable space, then such a regular version is guaranteed to exist.

9.3.3 Conditional distributions

Let Y: (\Omega, \mathcal H) \to (E, \mathcal E) be a random variable. Then conditional distribution of Y given \mathcal F \subset \mathcal H is any probability kernel L from (\Omega, \mathcal F) to (E, \mathcal E) such that:

L(\omega, B) \stackrel{a.s.}{=} \mathcal P_\mathcal F \{\omega': Y(\omega') \in B\}

If the conditional measure \mathbb P_{\mathcal F} has a regular version Q then the conditional distribution of Y is guaranteed to exist and a version of it is given by: L(\omega, B) = Q(\omega, Y^{-1} B)

If (E,\mathcal E) is a standard measurable space, then a (kernel) conditional distribution of Y is guaranteed to exist. In short, it suffices for the range space of a random variable to be standard.

9.3.4 Conditional distribution given random variable

Let X: (\Omega, \mathcal H) \to (D, \mathcal D) and Y: (\Omega, \mathcal H) \to (E, \mathcal E). Suppose that the joint distribution \pi of X, Y, for a probability measure \mu on (D, \mathcal D) and probability kernel K from (D, \mathcal D) to (E, \mathcal E) and A \in \mathcal D, B \in \mathcal E, takes the form: \pi ( A \times B ) = \int_A \mu(dx) K(x, B)

Then, define the kernel L by:

L(\omega, B) = K(X(\omega), B)

Then \mu is the marginal distribution of X and L is a version of the conditional distribution of Y given \sigma X.

For every positive function f \in \mathcal D \otimes \mathcal E measurable wrt the product sigma algebra, we can express the conditional expectation \mathbb E [f(X, Y) | X] = \mathcal E_{\sigma X}[f(X, Y)] = \int K(X, dy) f(X, y)

9.3.5 Conditional density

Suppose we have the joint probability distribution \pi of X, Y in the following form, where \mu_0 and \nu_0 are \sigma-finite: \pi (dx, dy) = \mu_0(dx) \nu_0(dy) p(x,y) \mathbb P( X^{-1}A \cap Y^{-1} B) = \pi(A \times B) = \int_A \mu_0(dx) \int_B \nu_0(dy) p(x,y)

Define m(x) = \int \nu_0 (dy) p(x,y). Then, \mu(A) = \int_A m(x) \mu_0(dx) defines the marginal probability distribution of X.

Define

k(x, y) = \begin{cases} \frac{p(x, y)}{m(x)} & m(x) > 0\\ \int \mu_0(dx') p(x', y) & m(x) = 0 \end{cases}

Then, \mathbb P(Y \in B | X) = \int_B \nu_0(dy) k(x, y).

9.3.6 Disintegration

Let \pi be a probability measure on the product space (D\times E, \mathcal D \otimes \mathcal E). If (E, \mathcal E) is standard, then there exists a probability measure \mu on (D, \mathcal D) and a probability kernel K from (D, \mathcal D) to (E, \mathcal E) such that

\pi(dx, dy) = \mu(dx) K(x , dy)

Proof

Take \Omega = D \times E, and for \omega = (x, y) \in \Omega, define the random variables X(\omega) = x, Y(\omega ) = y. Observe that Y (\Omega, \mathcal H) \to (E, \mathcal E).

Thus, there exists a (kernel) conditional distribution given \sigma X satisfying: L(\omega, B) \stackrel{a.s.}{=} \mathbb P_{\sigma X}(Y^{-1}B)

L(\omega, B) is a kernel from (\Omega, \sigma X) to (E, \mathcal E) so \omega \mapsto L_B(\omega) is measurable wrt \sigma X, and thus we can write L_B(\omega) as a function of X(\omega), say K_B(X(\omega)).

L(\omega, B) = K(X(\omega), B)

Define \mu(A) = \pi(A \times E) = \mathbb P \circ X^{-1}(A).

Now we need to prove for all rectangles (a p-system generating the product \sigma-algebra) \pi(A \times B) = \int_A \mu(dx) \int_B K(x , dy)

\begin{align*} \pi(A \times B) &= \mathbb P( X^{-1}A \cup Y^{-1} B)\\ &= \mathbb E \left[\mathbb 1_{X^{-1}A}(\omega) \mathbb 1_{Y^{-1} B}(\omega)\right]\\ &= \mathbb E \left[ \mathbb E_{\sigma X} [\mathbb 1_{A}(X(\omega)) \mathbb 1_{Y^{-1} B}(\omega)]\right] \qquad \text{repeated conditioning}\\ &= \mathbb E \left[ \mathbb 1_{X^{-1}A}(\omega) \mathbb E_{\sigma X} [\mathbb 1_{Y^{-1} B}(\omega)]\right]\qquad \text{conditional determinism}\\ &= \mathbb E \left[ \mathbb 1_{X^{-1}A}(\omega) \mathbb P_{\sigma X} (Y^{-1} B) \right]\\ &= \mathbb E \left[ \mathbb 1_{X^{-1}A}(\omega) K(X(\omega), B) \right]\\ &= \int \mathbb 1_A(X(\omega)) K(X(\omega), B) \mathbb P (d\omega) \\ &= \int \mathbb 1_A(x) K(X(\omega), B) \mathbb P\circ X^{-1} (dx) \\ &= \int_A \mu(dx) \int_B K(x, dy) \end{align*}

9.4 Conditional independence

9.4.1 Definition

\mathcal F_1, \dots \mathcal F_n are conditionally independent given \mathcal F \subset \mathcal H if for all positive V_i \in \mathcal F_i:

\mathbb E_\mathcal F [\prod_{i=1}^n V_i ] \stackrel{a.s.}{=} \prod_{i=1}^n \mathbb E_\mathcal F [V_i]

An arbitrary subcollection \{\mathcal F_t: t \in T\} is conditionally independent if every finite subcollection is conditionally independent.

9.4.2 Alternative definition

Instead of for all measurable functions, we can prove conditional independence from a p-system.

Let \mathcal C_i be a p-system containing \Omega that generates \mathcal F_i. Then \mathcal F_1, \dots \mathcal F_n are conditionally independent given \mathcal F if and only if for every set A_i \in \mathcal C_i for i= 1, \dots , n:

\mathbb P_\mathcal F(\cup_{i=1}^n A_i) = \prod_{i=1}^n \mathbb P_\mathcal F (A_i)

9.4.3 Subgrouping

\{\mathcal F_t : t\in T\} is independent given \mathcal F if and only if for every subpartition \{T_s: s\in S\} of T, \{\tilde{\mathcal F_s}: s \in S \} is conditionally independent given \mathcal F, where \tilde {\mathcal F_s} = \sigma (\cup_{t\in T_s} \mathcal F_t).

9.4.4 Coarsening

\{\mathcal F_t : t\in T\} is independent given \mathcal F if and only if \{\mathcal G_t : t\in T\} is independent given \mathcal F for every collection satisfying \mathcal G_t\subset \mathcal F_t for each t \in T.

9.4.5 Augmentation

\{\mathcal F_t : t\in T\} is independent given \mathcal F if and only if \{\sigma \bigg(\mathcal F_t \cup \mathcal F\bigg): t\in T\} is independent given \mathcal F.

9.4.6 Conditioning augmentation

\{\mathcal F_t : t\in T\} is independent given \mathcal F if and only if for all subsets S \subset T, \{\mathcal F_t : t\in T\} is independent given \sigma \bigg( \cup_{s \in S} \mathcal F_s \cup \mathcal F \bigg).

9.4.7 Equivalent definitions

The following statements are equivalent:

- \mathcal F_1, \mathcal F_2 are conditionally independent give \mathcal F.

- \mathbb E_{\sigma ( \mathcal F \cup \mathcal F_1)} [V_2] = \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_2] for all V_2 \in \mathcal F_2^+.

- \mathbb E_{\sigma (\mathcal F \cup \mathcal F_1)} [V_2] \in \mathcal F for every V_2 \in \mathcal F_2^+.

Proof

a \implies b

We assume \mathcal F_1,\mathcal F_2 are conditionally independent given \mathcal F.

By augmentation, we get that \mathcal G = \sigma(\mathcal F_1 \cup \mathcal F) and \mathcal H = \sigma(\mathcal F_2 \cup \mathcal F) are conditionally independent given \mathcal F. Now \mathcal F_2 \subset \mathcal H so by subgrouping, \mathcal G and \mathcal F_2 are independent given \mathcal F.

Consider a function V_2 \in \mathcal F_2^+.

For \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_2] to be the conditional expectation of V_2 wrt \mathcal G, it has to be measurable wrt \mathcal G and follow the projection property.

By definition of conditional expectation \mathbb E_\mathcal F [V_2] \in \mathcal F \subset \mathcal G, so \mathbb E_\mathcal F [V_2] is measurable with respect to \mathcal G.

Now, let us check the projection property- for every V_1 \in \mathcal G^+, we want: \mathbb E[V_1 \cdot \mathbb E_\mathcal F [V_2] ] = \mathbb E[V_1 V_2]

Since \mathcal G and \mathcal F_2 are independent given \mathcal F, we know

\begin{align*} \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_1 V_2] &= \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_1 ] \cdot \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_2] \\ &= \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_1 \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_2]] \qquad \text{conditional determinism}\\ \mathbb E[\mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_1 V_2]] &= \mathbb E[\mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_1 \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_2]] ]\\ \mathbb E[V_1 V_2] &= \mathbb E[V_1 \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_2]] \qquad \text{repeated conditioning}\\ \end{align*}

b \implies c

Assume \mathbb E_{\mathcal G} [V_2] = \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_2] for all V_2 \in \mathcal F_2^+. Then by the definition of conditional expectation, \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_2] and thus \mathbb E_{\mathcal G} [V_2] is measurable wrt \mathcal F.

c \implies a

Assume \mathbb E_{\mathcal G} [V_2] \in \mathcal F for every V_2 \in \mathcal F_2^+.

We need to check if \mathcal F_1, \mathcal F_2 independent given \mathcal F. So take V_1 \in \mathcal F_1^+, V_2 \in mathcal F_2^+.

Since \mathbb E_\mathcal G[V_2] \in \mathcal F:

\begin{align*} \mathbb E_\mathcal G[V_2] &= \mathbb E_\mathcal F[\mathbb E_\mathcal G[V_2]] \qquad \text{conditional determinism}\\ &= \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_2] \qquad \text{repeated conditioning}\\ \end{align*}

Since \mathcal F \subset \mathcal G and \mathcal F_1 \subset \mathcal G

\begin{align*} \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_1 V_2] &= \mathbb E_\mathcal F[\mathbb E_\mathcal G[V_1 V_2] ]\qquad \text{repeated conditioning}\\ &= \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_1 \mathbb E_\mathcal G[V_2] ] \qquad \text{conditional determinism}\\ &= \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_1 \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_2] ] \\ &= \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_1 ] \mathbb E_\mathcal F[V_2] \qquad \text{conditional determinism} \end{align*}